The beauty of paradox

by Alice Chauchat

10 years ago, as Alix and I were discussing what performance we would create together, we regularly stumbled upon a divergence between our respective takes on performance. The issue revolved around beauty and spectacle. Whereas I reacted strongly against risks of normalization (by affirming dominant canons), objectification (by staging the dancer as an object) and stultification (by lack of challenge to established convention), Alix kept her foot in the door of spectacle, arguing for the benefits of mystery and dream.

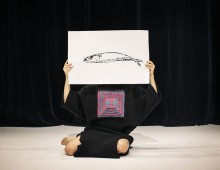

Crystalll, the piece that eventually resulted from these endless conversations, staged the tension between the desires and rejections we had been negotiating along the process, focusing on the status of the female body in the representational regime of arts. Alix performed this solo as an out-of-reach, idealized figure, walking a tightrope between embracing her position as object in the show, and affirming her subjectivity within this display.

Confronting aesthetic, political and/or ethical values seems an ongoing project throughout her work: nourishing contradiction, feeding paradoxes as necessary procedures to keep alive the questions of value, to destabilize them without canceling them out.

In The Visitants, Alix and Agata Maskiewicz practiced techniques of self-development as performance practices. The tension between their affirmed objective of authenticity or “coming closer to oneself” and the artificiality of the context opened a gap that questioned the very idea of a contradiction: the self that is present is that of a performer, developing indeed in relation to a gaze. In such a situation, there is no contradiction between presence and representation, artifice and integrity.

In Exit, created together with Kris Verdonck, the principle of revelation was pragmatically followed. The performance opens with Alix explaining in detail everything that will happen during the piece, before performing it as announced. Beyond the difference between hearing something being described and experiencing it, the frankness of the proposal is almost impossible to trust. Will she really do this? No surprise? And she does, and the surprise is that we do sleep as she offered we might (and by the way, wasn’t she wearing a different dress earlier?) Shining through the obvious is the ever-present possibility of things being other than they seem, or both at the same time. The dance luring us to watch it, it’s a nice dance and it’s well danced, is also made not to hold our attention too much, rocking us away, convincing us to stop watching.

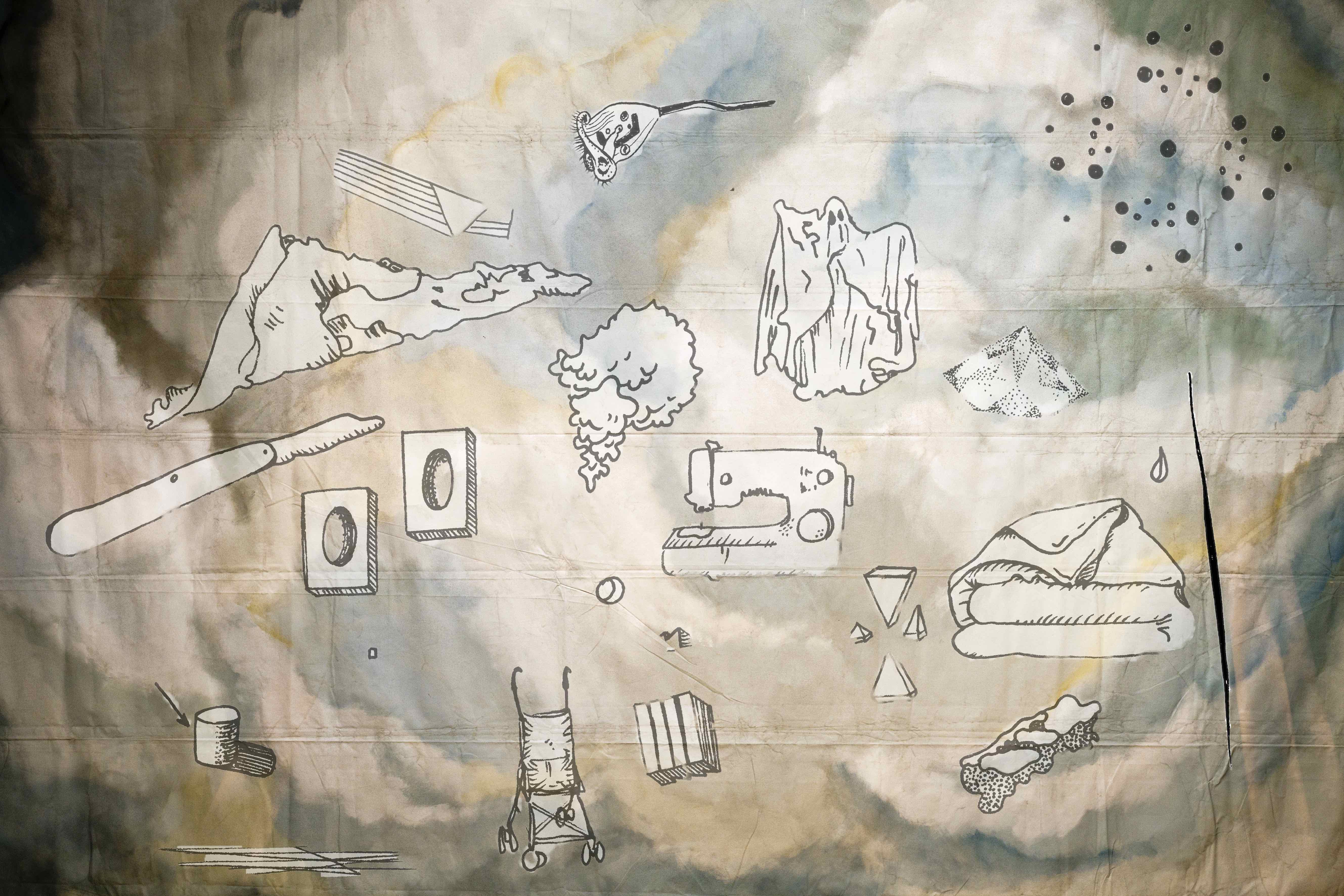

In the duet Monique, gestures of power such as tying the other’s body with ropes, shaping it into awkward positions or directing him, her, in a show of psychic manipulation, are performed with care, as a treatment. When the audience comes in, a performer is polishing the other’s nails: a servant, a friend, working on her to bring her closer to her, or to his own, projections? Then they exchange roles, she trims his mustachio and the same doubt is there. The dance will be one of manipulation. Gestures are crude in their form and delicate in their performance. References to the bondage culture suggest that its erotic dimension rests in the pleasure of surrendering rather in that of overpowering. The choreography of control is one of gentleness. It is exquisite and fetishistic in the minute attention to details of the body and of its organization. Such extreme formalism requires virtuosity. Virtuosity brings us back to issues of dance, performance and arts in general. Appearance and occultation are extremely dramatized. A bondaged loudspeaker is slowly pulled onto the stage, a performer’s face is being covered with great pathos. The drama of theater is being played, and the audience is directly addressed as a partner of the game.

Alix’s art is paradoxical. Paradoxes produce unrest, and this unrest is beautiful. It is mysterious. It makes us think and actively not know, which is a sensual experience.